Maria Bueno’s finest exploits are still being recalled over half a century later, one such tribute came from the well-renowned American tennis writer and author, Steve Flink, in his book entitled ‘The Greatest Tennis Matches of All Time’ (published in 2012), in which he lists the 10 greatest at Wimbledon.

The 1964 final featuring Bueno against Margaret Smith Court ranks seventh in terms of Wimbledon matches and twenty-seventh overall.

We are indebted to Steve for allowing this website to reproduce the chapter for Maria’s fans.

Steve Flink writes in Chapter Ten of ‘The Greatest Tennis Matches of All Time’ (published in 2012):

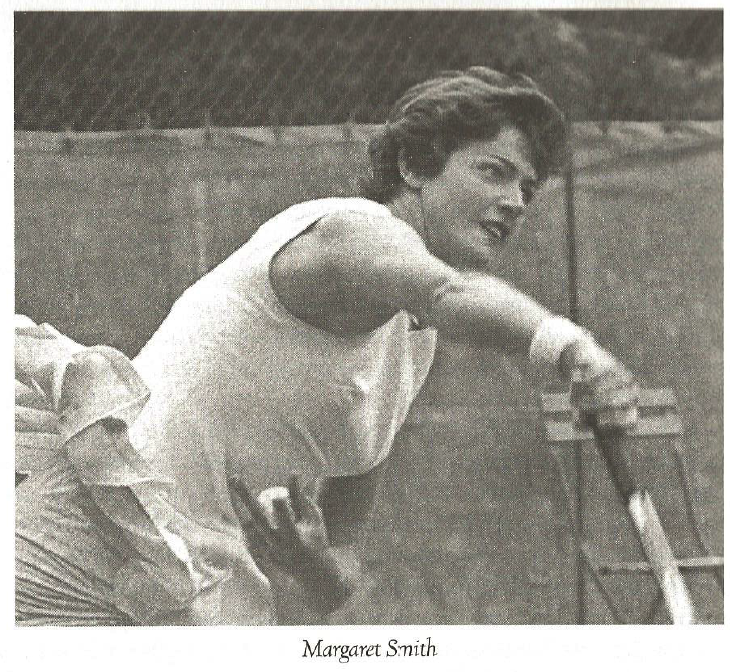

Maria Bueno vs. Margaret Smith

WIMBLEDON FINAL. JULY 4, 1964

The graceful artist from Brazil took on the tall athlete from Australia. As always, they brought out the best in each other.

PROLOGUE

Over the first half of the 1960s, two women set the agenda and settled more big matches than any other players. They delighted galleries all over the world with their contrasting personalities yet similarly aggressive styles. They attacked each other’s games unwaveringly and intelligently, and more often than not brought out the best in each other. Brazil’s Maria Bueno and the Australian Margaret Smith were clearly the preeminent players of that era, taking the women’s game into another realm, a slower but in many ways more captivating type of serve-and-volley tennis than that of the men. Bueno Smith matches were not to be missed. They added value to the major championships simply by showing up.

Both players had made their mark by the time they clashed in the 1964 Wimbledon final. Smith, who grew up in New South Wales, Australia, was the daughter of a foreman at a cheese and butter processing plant. Her first tennis racket was given to her by a sympathetic neighbor. She began refining her game at a private tennis club not far from her home. When she was eight years old, she would creep under the fence of the courts to play against boys who were members of the club. She won her first tournament before she was ten.

Margaret was a natural left-hander when she began playing the game as a young girl. She was persuaded to switch the racket to he right hand by boys in her neighborhood who made fun of her. As she explained in her book, Court on Court, A Life in Tennis (with George McGann) “I got so many taunts that I finally switched the racket to my right hand and played that way thereafter. I’ve always felt that if I had remained a left-hander I would never have experienced so many problems with my serve.”

Difficult or not, Smith made the adjustment. By 1964, she had secured five consecutive Australian Championships. Earlier that year in Brisbane, she won with remarkable command of the court in a 6-3, 6-2 final-round triumph over countrywoman Lesley Turner. A month before that she had taken her second singles championship on the red clay of Roland Garros, winning the French Championships in Paris with a come-from-behind, three-set victory over Bueno. Two years earlier, she had erased a match point against her in a three-set win over Turner on the same court.

In 1962, Margaret had ruled at Forest Hills, taking the U.S. Championship title. On that occasion, Smith stopped the talented American, Darlene Hard – Bueno’s accomplished doubles partner – in a hard-fought, 9-7, 6-4 final. In the 1963 Centre Court title match at Wimbledon, she was too good for an American named Billie Jean Moffitt (soon to be Billie Jean King). Smith triumphed, 6-3, 6-4.

She was well on her way to a record-breaking career. Not yet twenty-two, she had nine major singles titles in her possession. She was nearly six feet tall, and despite her large frame (the press constantly referred to her as statuesque), she covered the court swiftly. She was particularly adept at blanketing the net, making the stretch volley with regular and unprecedented success, showing her opponents how tough it was to drive the ball past her. A superb athlete, Smith could count on her strength to carry her through long afternoons of competition.

Bueno’s father, Pedro, was a veterinarian who had an interest in tennis. Though demure and trim, she grew tall enough at 5’ 7” to make her presence known. She, too, had enjoyed multiple successes in England and elsewhere in the years leading up to a vintage 1964 Wimbledon. While Smith was more of a programmed player who won her matches through self-discipline and careful application of her skills, Bueno at her core an artist. A fluid shotmaker who often played points spontaneously, she took great pleasure in being inventive and bold. She was something of a ballerina on the tennis court (not unlike Suzanne Lenglen), gracefully gliding through many of her matches, making shots effortlessly. With this deceptively flowing ability, Bueno captured Wimbledon in i959 and 1960. The following year, she was almost always in bad health and there was some talk that she might not compete again . But she returned with vigor in 1962, and was soon on her way to the top of her game.

In the 1959 Wimbledon final, Bueno had halted the No. 4 seed Darlene Hard 6-4, 6-3 to win her first major crown. She was only nineteen, and seeded sixth in that event. The Brazilian conceded sets in her second and third round matches, but did not drop another in her last four appearances as her game seemed to improve every time she stepped on court. The following year, she returned as the favorite, seeded No. 1. She lost only one set in that tournament – to the No. 4 seed Christine Truman in a 6-0, 5-7, 6-1 semifinal victory – and defeated No. 8 seed Sandra Reynolds of South Africa 8-6, 6-0 in the final.

Bueno’s success was international. She had also captured two U.S. Championships at Forest Hills. In 1959, she had a close call with the American Jeanne Arth before escaping 4-6, 6-3, 7-5 in the third round. She took off confidently from there, not losing another set, defeating Hard and Truman in decisive meetings at the end. Four years later, she got her title back at Forest Hills, coming through with a pair of clutch victories to close out that first-rate tournament. In the semifinals, Bueno took on the formidable Englishwoman Ann Jones, a left-hander who knew how to use every inch of the court. Six years later, Jones would crown her career by winning Wimbledon, but in this collision she failed to make good on an early lead over an out-of-sorts Bueno. Jones won the first set and was not behind until 6-5 in the final set. Bueno prevailed 9-7 in the third. In the final, she had another top notch match against Smith, who had beaten her the previous year in the semifinals. Bueno was dazzling in this duel, and she clipped Smith 7-5, 6-4.

On that occasion, the Brazilian was down 1-4, 0-30 in the second set, about to be pushed into a final set by the persistent Australian. Bueno simply turned up her intensity, sharpened her familiar shots, and did not lose another game. It was among the most celebrated sets of her career, and it left Smith dazed and disconsolate when it was over. Bueno loved nothing more than big match conditions, delighting in performing with her back to the wall. Bueno’s record worldwide was comparable to Smith’s; the difference between them was Smith’s mastery of her native turf, her complete domination of the Australian Championships.

As they approached this Wimbledon Centre Court clash, their accomplishments elsewhere in the Grand Slam game were similar. Smith had won two French Championships along with one triumph at both Wimbledon and Forest Hills. Bueno had her twin triumphs at Wimbledon and Forest Hills but had not prevailed in Paris. The moment had arrived for them to collide again in a major final, and they both were ready.

THE MATCH

Appropriately, Smith was the top seed at Wimbledon in 1964, while Bueno was placed second. On her way to the final, Smith had only one match that gave her cause for consternation. In the third round, she came up against 1962 titlist Karen Susman, who was not playing regularly anymore on the circuit. Susman was still a seasoned grass court player. She gave the Australian a thorough test in the opening set, looking very impressive in the process, but Smith prevailed 11- 9, 6-0. She moved on easily to the semifinals where she met Billie Jean Moffitt. The American had beaten the top-seeded Smith in the second round two years earlier, then reached the final the previous year before losing to Margaret 6-3, 6-4. This time, Smith won by the identical score.

Bueno played superlatively all through the tournament, until she faced the canny Lesley Turner, the No. 4 seed, in the semifinals. Turner’s forceful, flat ground strokes were very effective on the low bouncing grass, troubling Bueno all through the first set. Bueno shrewdly made adjustments and rebounded 3-6, 6-4, 6-4. The final that all close followers of the game had wanted was on the line. Could Bueno summon the inspiration to overcome Smith with her superior, if streakier, shot-making? Would Smith gain the upper hand with her physical advantages, her reach at the net, her greater size and strength? Who would stand up better to the pressure of a Wimbledon final, an experience unlike any other in the sport?

At the outset, Smith was riddled with apprehension, suffering from serious anxiety as she often did before Centre Court matches. In the opening game, Margaret double faulted on break point, her second serve falling feebly into the net. The Australian broke back at love for 1-1, boosted visibly by a backhand half volley pass as she attacked behind her return for 0-40. The revival was brief. Flashing a superb backhand passing shot with slice down the line for break point, followed by a well-concealed backhand slice lob over Smith’s head, Bueno had the break again for 2-1. The Brazilian mixed her game adroitly to hold for 3-1, but serving in the sixth game she wasted three game points and Smith drew level at 3-3.

At 4-4, Smith’s emotional fragility surfaced again. At 15-40, she attempted an American twist second serve which landed in the wrong service box, ten feet wide. Bueno was not going to waste her opportunity to serve out the set. At 5-4, 40-30, she stayed back on her second serve, then worked her way in behind a backhand slice approach which clipped the sideline. Smith’s running forehand passing shot was wide. Bueno had secured the set, 6-4.

Troubled by her loss of the opening set, Smith fell behind 15-40 in the first game of the second. Here she was helped by an overanxious Bueno, who missed a backhand return and a backhand passing shot. At game point, Smith found her confidence, making a classic forehand volley winner at full stretch. She broke in the next game with three soundly struck passing shots for 2-0, then served a commanding love game for 3-0 as she connected with every first serve.

Sensing the possibilities at that stage, Smith broke again for 4-0 with a backhand return winner past a charging Bueno. Soon Margaret stood at 4-0, 40-15. Bueno’s piercing returns brought her back to deuce. Smith double faulted, saved the first break point, only to double fault again at break point down. Bueno held on from 30-30 for 2-4. Smith sorely needed to reassert herself in the seventh game on serve.

She fell far short of that goal. Off the mark with four out of five first serves, double faulting once more, she was broken again by a tricky chipped backhand return to her feet. At 3-4, Bueno missed seven of eight first serves, but she survived that game by producing some excellent play from the backcourt. Bueno had climbed to 4-4. Would she run out the match as Smith dwelled on her lost chances?

The ninth game stretched into nine deuces. Bueno reached break point five times. Yet Smith remained steadfast, connecting on seventeen of twenty-two first serves, and finding other ways to unsettle Bueno. On game point , the Australian stayed back after a first serve, a tactic that worked as the Brazilian drove a forehand return wide. At 5-5, Smith was obstinate on serve again, holding from 15-40, saving two break points. She had fought her way to 6-5.

Smith held at love for 7-6 with deft volleying, then held at love again for 8-7 by scampering in alertly to cover a drop shot before snapping an overhead into the clear. With Bueno serving at 7-8 Smith increased the pressure. She moved in behind her return of Bueno’s second serve to put away an emphatic forehand volley. After Bueno netted a back hand volley, Smith drove a stinging forehand passing shot down the line to force Bueno into an errant volley. Despite squandering the 4-0, 40-15 lead, Smith had reached far inside herself to seal the set.

Until the middle of the final set, Smith seemed to be the better player. She lost only two of fourteen points in three dominant service games, connecting on thirteen of fourteen first serves. She was getting better depth on her serve, closing in tighter for the first volley, forcing Bueno into more mistakes . At 1-2, Bueno was break point down. She saved it with a flourish, punching a penetrating first volley, retreating rapidly for a lob from the Australian and smashing it away. Bueno lifted herself to game point with a strong forehand volley placement off a Smith down-the-line passing shot. Bueno held on for 2-2.

Smith served an ace to hold for 3-2. Bueno was not daunted. She held at love for 3-3 with a flat backhand passing shot, then broke Smith for 4-3- Margaret had served-and-volleyed before moving back for an overhead as Bueno lifted a lob high into the air. Smith’s smash lacked severity, and Bueno drove a forehand crosscourt that forced Margaret into the backcourt. Bueno came in and Smith missed a backhand pass. The net had been taken away from her. The match seemed to be slipping away as well.

Bueno moved to 5-3 at the cost of only one point. In concluding that game, she was letter perfect. The Brazilian charged into the net behind her serve, made a solid, deep volley, and knew where Margaret was going with the passing shot before Smith did. Bueno was on top of the net for a scintillating forehand volley winner. Smith served to save the match at 3-5, double-faulted to 0-30, and fell behind 15-40, double match point. Bueno lofted another effective lob, forcing Smith to play a soft overhead. Anticipating that response, Bueno moved in and played a backhand half volley approach from mid-court.

The ball floated high over the net but Smith was too stunned to react. She stood there deep in the court, frozen, realizing she had no chance to reach the ball. Bueno had hit a nearly impossible shot at match point to prevail 6-4, r7-9, 6-4. In collecting the last four games in a row, Bueno had won sixteen of nineteen points. Her streak to the finish line was reminiscent of her Forest Hills victory over Smith the year before. Bueno was the Wimbledon champion for the third time, and had never been better.

As the eloquent David Gray wrote in The Guardian, “Miss Bueno was scoring points with capricious ease. The Brazilian spent points as wastefully as ever, but in the crisis of the match she invariably found it possible to produce luxurious quantities of shots which were rich and imaginative, graceful and deadly. She was the more effective server, she did not miss a smash and, in the recollections of even the oldest members, no woman has hit so many beautiful and piercing forehand volleys. She stirred the Centre Court as she did in the first dazzling days of her royalty.”

EPILOGUE

Later that summer, Bueno underscored her status as the best player in the world by winning Forest Hills for the second straight year. In the final, she routed the capable American Carole Graebner 6-1, 6-o. Smith – who was beaten only twice all season-was ousted in three sets by Susman in the round of sixteen. The Australian had captured the Australian and French Championships but Bueno had taken the two most important titles in tennis by coming through at the All England Club and Forest Hills. She had lost a significant meeting to Smith in Paris, but had gathered the two prizes she valued the most. It was her most productive season.

The following year, Smith was leading Bueno 5-2 in the third set of the Australian Championships final when the Brazilian had to retire with an injury. Smith went on to win Wimbledon by taking Bueno 6-4, 7-5 in a well-played final. She also took the U.S. Championships with a final-round win over Billie Jean Moffitt. Her lone Grand Slam defeat was in Paris, where she lost the final to the meticulous backcourt play of Turner. Smith was nearly invincible across that season, winning fifty-eight matches in a row, and capturing eighteen tournaments during the year.

Bueno, hampered severely that year by a knee injury, underwent surgery. She was not the player she had been in 1964, but the following year she was revitalized. In the 1966 Wimbledon, Smith and Bueno were seeded first and second again. Bueno moved as expected 10 the final but Smith was ousted by Billie Jean Moffitt King, who had married in the autumn of 1965. King beat Bueno for the title.

The Brazilian was in peak form at Forest Hills, winning the U.S. Championship for the fourth and final time, capturing her last Grand Slam championship. In the final, she was down 0-2 in the first set against the determined Texan Nancy Richey. From that juncture , Bueno’s virtuosity was too much for her doubles partner, with whom she had won at Wimbledon two months earlier. Bueno soared to a 6-3, 6-1 victory. She was not yet twenty-seven when she collected that crown with bright sequences of freewheeling shotmaking. It seemed entirely possible that Bueno would celebrate another five years in the upper echelons of the game.

In fact, she would no longer play at that level. Beginning in 1967, she was hindered by a wide assortment of injuries. The primary problem for Bueno was her arm. That year, she lost in the round of sixteen at Wimbledon to the rapidly rising American Rosie Casals. She withdrew from the U.S. National Championships at Forest Hills, where she was seeded sixth. The pain was persistent near her shoulder. Bueno was drifting out of tennis, much to the dismay of her large legion of admirers.

The following year, she did play respectably in the majors. King defeated her in the quarterfinals of the first French Open. Richey beat her in the same round at Wimbledon. At Forest Hills, she performed better than she had for a long while. At that initial U.S. Open, she was seeded fifth. In the quarterfinals, she upset the No. 4 seed Margaret Smith Court 7-5, 2-6, 6-3 – their last meeting of consequence. Maintaining that form in her semifinal session with King, Bueno took the first set before bowing 3-6, 6-4, 6-2. She was ranked in the top five in the world for the year.

The pain in her arm persisted . Buena’s career was essentially over. She did make what amounted to a sentimental comeback in 1976 and 1977, when she was in her late thirties, but the majestic match playing qualities were gone. Her comeback was brief, although it must have been worth her while since fans greeted her appearances with genuine warmth. Bueno remained a powerful presence on the tennis stage, even if her skills and speed had been diminished.

Smith was another story. She continued her complete domination of the Australian Championships, extending her streak to seven consecutive titles in 1966. In 1967, Smith married Barry Court, and pondered retirement for a while. By 1968, with Open Tennis a reality, Margaret Smith Court was not content to rest on her laurels. She turned twenty-six in the middle of that year. She had not realized all of her ambitions, and was determined to come back to the courts triumphantly, sharing the victories with her husband, who joined her on the road and provided much encouragement. Barry Court wanted his wife to enjoy her tennis, and she did.

The first year of the open game was lukewarm for Margaret. She was shy of her best as she reacquainted herself with the rigors of match play. Not present for the French Open, she was seeded second at Wimbledon behind King, appearing for the first time on the draw as Mrs. B. M. Court. In the quarterfinals, she fell surprisingly to countrywoman Judy Tegart 4-6, 8-6, 6-i. She won the U.S. Nationals over Bueno, but the Brazilian retaliated in the quarterfinals of the U.S. Open. Court took her place, however, among the top five in the world despite her lackluster showings in the two foremost tournaments.

In 1969, she had one of her greatest seasons, sweeping three of the four major championships, losing her lone “Big Four” match to the British left-hander Ann Jones in the semifinals of Wimbledon. At the age of twenty-seven , she had already captured a total of sixteen major singles titles.

There was much more in store for this woman of quiet dignity and high ambitions.

Extracted from ‘The Greatest Tennis Matches of All Time’ by Steve Flink (published in 2012) – Chapter Ten

Extracted from ‘The Greatest Tennis Matches of All Time’ by Steve Flink (published in 2012) – Chapter Ten